“[Labs] are like sausages; it is better not to see them being made.”

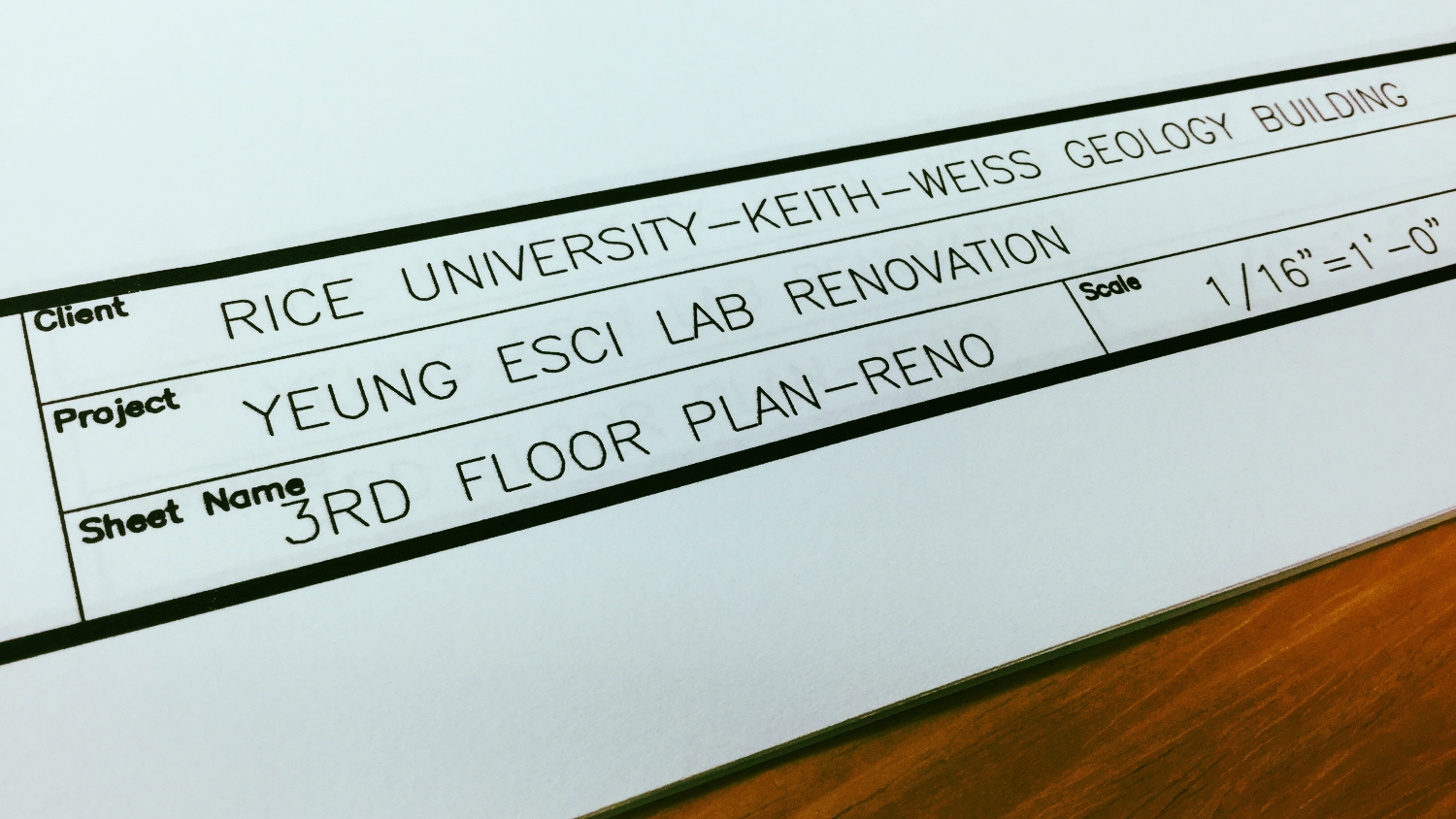

We had the latest in a series of laboratory design meetings today. The renovations now seem like quite an undertaking: We had probably twenty people in that trailer -- architects, contractors, engineers, building managers, etc. -- to work on plans we're going to send to the city for permitting. You'd be surprised at the kinds of things a young assistant professor has to decide, weeks into his job, that not only dwarf his net worth, but also set the stage for success or failure down the road (let's hope for success).

Before I get into that, however, I want to tell you about my kitchen. It's old. It's dark. The drawers are sticky. The cabinets don't always close all the way. There's not enough counter space. Plus, I'm still getting used to the (awkward) distances between the fridge, sink, and cooktop. Cooking in it is actually pretty uncomfortable.

Contrast this with my last kitchen, which was bright, efficient, and most importantly, heavily used: I cooked more things for more people in that tiny kitchen over the past decade than I can remember, and I find myself longing for its drawers, its layout, and its...flexibility. One morning I'd be baking croissants, and that afternoon I could be preparing hors d'oeuvres and plating dishes for guests with little trouble. It was designed to be a functional, flexible kitchen.

I want the lab to be the same: structured yet flexible, and a pleasure to work in. Like a kitchen, it will have fixtures (a mass spectrometer, fume hood, vacuum lines, etc.) that one will likely use every day. It needs ample storage, power, and working spaces for any of the myriad tasks we might be doing (running an experiment, prepping sampling vessels, developing techniques, etc.). At the same time, it must adapt as new fixtures are added to it and the focus of the research inevitably shifts over time. Given the number of hours my group and I will be spending in there, we owe it to ourselves to make our workspace a good one.

It is easy to lose the forest for the trees amongst the deluge of micro-decisions one must make when building a lab, such as: What vacuum pump or valve should I buy, how tall should the bench heights be, what material and diameter do these tubes need to be, how can we fit the mass spec through these doors, where is everyone going to sit, will we be disturbing the labs next door when we WHEEL IN THE GIANT TANKS OF LIQUID NITROGEN I CAN'T EVEN -- you get the idea. These decisions are maddening. But someone has to decide.

I try to make a couple of these decisions a day so I don't get sucked into the weeds so easily. I have also had to accept that I'll make some mistakes. I'll design some things that will never used, while I'll also leave some blank spots that will stay that way. All we really need is a place to put and to plug in the mass spec; the rest will work itself out once we move in. That is the story I tell myself, at least.